It might have been written a hundred times, easily, on that enormous face. Humpty Dumpty was sitting, with his legs crossed like a Turk, on the top of a high wall -- such a narrow one that Alice quite wondered how he could keep his balance -- and, as his eyes were steadily fixed in the opposite direction, and he didn't take the least notice of her, she thought he must be a stuffed figure, after all.

`And how exactly like an egg he is!' she said aloud, standing with her hands ready to catch him, for she was every moment expecting him to fall.

`It's very provoking,' Humpty Dumpty said after a long silence, looking away from Alice as he spoke, `to be called an egg -- very!'

`I said you looked like an egg, Sir,' Alice gently explained. `And some eggs are very pretty, you know,' she added, hoping to turn her remark into a sort of compliment.

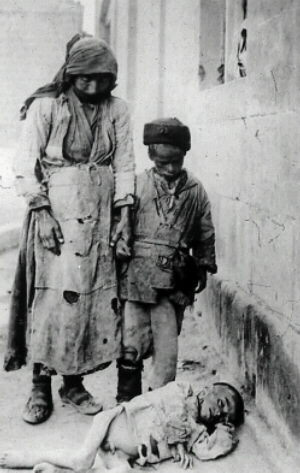

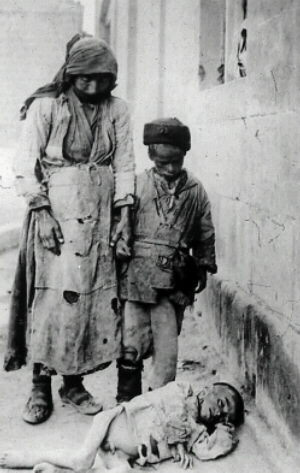

Ssssh. Can you hear us? The sounds we make our muffled. There is not much room for us here in these mass graves. We are stuffed together, face to face, arms strewn across one another, feet covering bellies. We are the dead of 1915. The smell of our rotting bodies has long ago dissipated; the flies have moved on. There is grass over the places where we were thrown into the earth.

But, if you listen closely, you can hear our murmurs. It is not so much justice we want. Justice is for the living. What does it benefit the dead to be granted justice after we are gone?

What we want is to be acknowledged. We are here. And we did not get here on our own.

So what would you have it be called?

Armenians claim that as many as 1.5 million of their ancestors were killed between 1915-1923 in an organized campaign to force them out of eastern Turkey and have pushed for recognition of the killings around the world as genocide.

Turkey acknowledges that large numbers of Armenians died, but says the overall figure is inflated and that the deaths occurred in the civil unrest during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Don't call it genocide, the Turks say, and if you do, you shall be jailed. It insults "Turkishness" to say that they were capable of killing us like that. You cannot even talk about it in your fiction:

The charges stemmed from remarks made by an Armenian character in Shafak's novel The Bastard of Istanbul, published in March. "I am the grandchild of genocide survivors who lost all their relatives at the hands of Turkish butchers in 1915," Dikran Stamboulian says, referring to the controversial topic of the mass murder of Armenians in the last days of the Ottoman Empire.

"It was an absurd reason to start a trial and a very sensible way of ending it," said Shafak's husband, Eyup Can, outside the heavily guarded Istanbul courthouse.

Shafak was the latest public figure targeted by a group of nationalist lawyers using the notoriously vague article 301 of Turkey's penal code. Protesters linked to the group had attacked novelist Orhan Pamuk when he went on trial last December. Around 300 riot police were on hand yesterday to prevent violence, with dozens more plainclothes police inside. Joost Lagendijk, a Dutch MEP attacked at Pamuk's trial, was given eight bodyguards.

It is not allowed. It did not happen.

The irony of the latest development would kill us if we were not already dead. The French have introduced a bill that would punish those who deny that it was genocide.

Turkey called Monday on the European Union to oppose French legislation that would outlaw denials that World War I-era killings of Armenians amounted to genocide.

Lawmakers in France, which has some 400,000 citizens of Armenian origin, have introduced a bill to penalize Armenian genocide denial with fines and jail terms. Turkey, which says the deaths came during a period of civil unrest and don't constitute genocide, asked the European bloc it seeks to join to weigh in on its side.

''We expect the European Union to express its opposition against such a development that restricts freedom of expression in France, because it contradicts key values of the EU,'' said Justice Minister Cemil Cicek, who also serves as the government's spokesman.

Do you not see why that is so funny? Call it genocide in Turkey and go to jail. Deny it was genocide in France and go to jail.

In the meantime, we are still dead. Still here. Still waiting.

The Turkish Prime Minister, who apparently believes as your president does, that a lie repeated repeatedly eventually becomes the truth has reacted thusly:

ISTANBUL, TURKEY // Turkey's prime minister vowed today to fight against what he called a "systematic lie machine" pushing to label Turkey's World War I-era killings of Armenians as genocide.

And still, we are dead.

Hrant Dink, who last year was prosecuted for talking about the genocide, has accused the French of hurting Armenians, of killing dialogue, by its insistence on trying to make it a crime to say that our deaths were not genocide.

Commenting on the "genocide denial bill," which is scheduled to come before the French Parliament October 12, Dink said "When this bill appeared first, we were fast to declare as a group that it would lead to bad results......As you know, I have been tried in Turkey for saying the Armenian genocide exists, and I have talked about how wrong this is. But at the same time, I cannot accept that in France you could possibly now be tried for denying the Armenian genocide. If this bill becomes law, I will be among the first to head for France and break the law. Then we can watch both the Turkish Republic and the French government race against eachother to condemn me. We can watch to see which will throw me into jail first.....I really think that France, if it makes this bill law, will be hurting not only the EU, but Armenians across the world. It will also damage the normalizing of relations between Armenia and Turkey. What the peoples of these two countries need is dialogue, and all these laws do is harm such dialogue."

But how can you have a dialogue with people who say your words are meaningless, that they are lies, that they are make-believe? How can their be dialogue when the other side has closed their ears to your truth?

Peter Balakian, who has written much about what happened to us, had this to say:

I think any true and meaningful dialogue can only happen if there is truth. We can't have debate without truth. Those who come to converse around a table must acknowledge the truth about the Armenian genocide and the moral nature of what genocide is, and then we can move forward.

Balakian told our stories in his book, Black Dog of Fate. It is not to be read by the faint of heart.

In the summer of 1915 in Diarbekir, every day you heard about Armenians disappearing. Shopkeepers disappearing from their shops in the middle of the day. Children not returning from school. Men not coming back from the melon fields. Women, especially young ones, disappearing as they returned from the bath. Shops had been looted by Turks more frequently that year. The pastry shop on Albak Street had been robbed and burned. The carpet store near the mosque had been broken into and cleaned out. Farms in the outlying valley had been stripped of their goats and sheep by Kurdish bandits, and everyone knew this had been sanctioned by the Vali. In the middle of the day a teacher at the Armenian school, Kanjian, was shot to death by the son of the mudir. No reasons given. No action taken. Mr. Kanjian's body was thrown in a wagon by the zaptieh and driven around the market square... Whenever we passed near a eucalyptus tree I gathered some leaves so that at night I could suck on them to get water in my mouth. I lay on the desert ground at night, sucking a eucalyptus leaf and staring at the moon. The moon is terribly bright in August in the desert around the Euphrates. All that month it grew each night. It followed us. It was a wolf's eye. It was the opal charm of a Turkish sorceress. Some nights it was a damask seal and some it was a Persian charger stripped of its blue. It was scouring and harsh on the weeds and rocks, and the few animals that darted through looked like unreal silvery creatures. I lay on my back and felt the grooves of my cuts made by the Turkish whips ease onto the hard ground, and I stared at the moon. Often I unfolded the piece of the kilim. It was the piece I used under the lamp on my nightstand in my bedroom. I held it up to the moonlight and looked at the colors and thought of my bedroom windows, one looking out to the street and the other into the fruit trees of our courtyard. It was just a simple kilim of aubergine and saffron medallions. In one latch-hook medallion there was a green scorpion, in the other a red scarab. In the moonlight the colors were eerie, and after a while they seemed to float in the black air and then drip like roman candles.

One night as I sucked on a eucalyptus leaf and stared at my kilim in the moonlight, I felt the boot of a gendarme against the side of my neck. I rolled over so as to hide my face in the ground. But the boot continued to kick me and then to step on my head. As I buried my head more fiercely in the ground, the boot hooked me under the chin and pried me up, and the next thing I knew I was looking up at a man whose mustache looked silver in the moonlight. I watched him unbuckle his pants and I shut my eyes and the next thing I knew a stream of hot piss shot into my nose and over my face. The cuts on my neck and cheeks began to sting and my eyes burned. Soon my hair was like a sticky mess of rancid flax. When he finished he kicked some dirt onto my face, and I lay there squeezing my kilim, which was also wet, and I felt a small breeze blow over my face. For a long time I did not open my eyes.

When I did, I took a eucalyptus leaf I had saved and wiped my eyes. When I looked up, the moonlight had turned the sky white and I could see my mother's face as if it floated on the white lace of our dining table. She was saying to me: Let them take you, let them take you, we will bring you back at Easter. Then the moon turned red as my taffeta dress, and my love had come in green velvet gloves and the scarf that hung in the walnut tree.

Run, run run the little chicken said. Your cheeks are like apples, and the wind takes your golden hair and sends it to the mountains.

From seven stores, I gathered silver and made a ring and put it on pearl's finger.

The moon stared at me all night. In the morning I woke inside the piss-gummed web of my hair, and I sucked on the eucalyptus leaf to make some saliva to clean off my face. Later I found some weeds, and I ground them up and spread them in the wounds enflamed by the piss.

One night I was raped. I prayed every night to the Virgin Mary and to Jesus and to God. And they answered my prayers. After this I felt some mindless will to survive.

And still we lie. In the dirt. Our bones turned to dust. Many of us will never be found. And if you cannot find us, if you cannot find the evidence that we were the victims of genocide, well, then how can you say it was so? And even if you do find the evidence, even if you were to be confronted with thousands of our skeletons, scattered across the horizon, hanging from the trees, the bodies of mothers and children and old men and old women and young men and ... and ... everyone. What then would you call it?

The French and the Turks will slap economic sanctions on one another, they will rail and hiss and spit at one another, they will throw the word "genocide" back and forth, and they will hold a mirror to each other's face and say, "You did this. Look." Algeria rhymes with Armenia. But no one will look. And we will still, still be dead.

It is, after all, a word. Just like justice, which is not for us. But please, please, can we not be allowed to claim the word "genocide" so that the enormity of what was done to us can be comprehended?

`When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, `it means just what I choose it to mean -- neither more nor less.'

`The question is,' said Alice, `whether you can make words mean so many different things.'

`The question is,' said Humpty Dumpty, `which is to be master -- that's all.'...

`That's a great deal to make one word mean,' Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

`When I make a word do a lot of work like that,' said Humpty Dumpty, `I always pay it extra.'